Prebiotics vs Probiotics: What’s the Difference?

Prebiotics vs Probiotics: What’s the Difference & Why You Need Both

The terms prebiotics and probiotics are often used interchangeably, but they represent very different — and complementary — roles in microbiome health.

In simple terms, probiotics add bacteria, while prebiotics determine whether those bacteria can survive and function.

Understanding this distinction explains why many gut-health strategies fail when they focus solely on bacteria, without supporting the microbial environment those bacteria need to remain active.

Common Questions About Prebiotics vs Probiotics

What is the main difference between prebiotics and probiotics?

Probiotics are live microorganisms, while prebiotics are non-digestible fibers that feed beneficial gut bacteria. Probiotics introduce bacteria; prebiotics shape the environment that allows those bacteria to function.

Do I need prebiotics if I already take probiotics?

Yes. Without prebiotics, introduced probiotic strains often fail to persist or remain metabolically active. Prebiotics provide the substrates required for microbial growth and function.

Are prebiotics and probiotics the same as fiber?

Not exactly. Some fibers act as prebiotics, but not all fiber selectively feeds beneficial microbes. Prebiotics refer specifically to fibers that are fermented by beneficial bacteria.

Why do probiotics sometimes not work?

Probiotics may fail when the gut environment lacks fermentable substrates. This phenomenon, known as colonization resistance, means newly introduced bacteria pass through the gut without establishing long-term residence.

Is it better to take prebiotics or probiotics?

This is the wrong question. Long-term microbiome health depends on both: probiotics provide microbial inputs, while prebiotics enable those microbes to function effectively.

What Are Probiotics?

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.

They are most commonly delivered as:

-

fermented foods

-

dietary supplements

-

targeted synbiotic formulations

Probiotic strains can influence digestion, immune balance, and microbial competition. However, their effectiveness depends heavily on whether they can survive, adapt, and remain metabolically active in the gut.

Many probiotic strains exert temporary effects rather than long-term colonization.

What Are Prebiotics?

Prebiotics are non-digestible compounds — primarily specific dietary fibers — that selectively nourish beneficial gut bacteria.

Unlike probiotics, prebiotics are not organisms. They are substrates that reach the colon intact and are fermented by resident microbes.

The foundational definition of prebiotics was introduced by Gibson et al. in the Journal of Nutrition, emphasizing selective microbial utilization and host benefit.

A deeper explanation of how prebiotics feed the microbiome is covered in the pillar article:

https://akkermansia.life/blogs/blog/prebiotics-explained-how-they-feed-the-gut-microbiome

Key Difference: Organisms vs Environment

The simplest way to understand the difference:

-

Probiotics add bacteria

-

Prebiotics shape the environment in which those bacteria live

Without an appropriate microbial environment:

-

introduced probiotic strains may fail to colonize

-

beneficial species may remain metabolically inactive

-

microbial balance may not improve sustainably

Research on colonization resistance — the gut microbiome’s ability to prevent newly introduced bacteria from establishing long-term residence — shows that introduced microbes often pass through the gut without persistence when substrates are lacking.

Why Probiotics Alone Are Often Not Enough

Many people report minimal or inconsistent results from probiotics. This is not necessarily because probiotics are ineffective, but because the gut ecosystem is undernourished.

Without adequate prebiotic intake:

-

beneficial bacteria cannot expand

-

short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production remains low

-

gut barrier support is limited

As a result, probiotics may provide transient effects rather than long-term adaptation of the microbiome.

From Strain-Centric to Ecosystem-Supporting Probiotics

This limitation has driven a shift in modern probiotic design from strain-centric models to ecosystem-supporting approaches.

Rather than focusing solely on introducing new bacteria, ecosystem-based probiotic formulations aim to support the microbial environment itself — including mucosal integrity, fiber fermentation, and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production — which determines whether beneficial microbes can remain metabolically active.

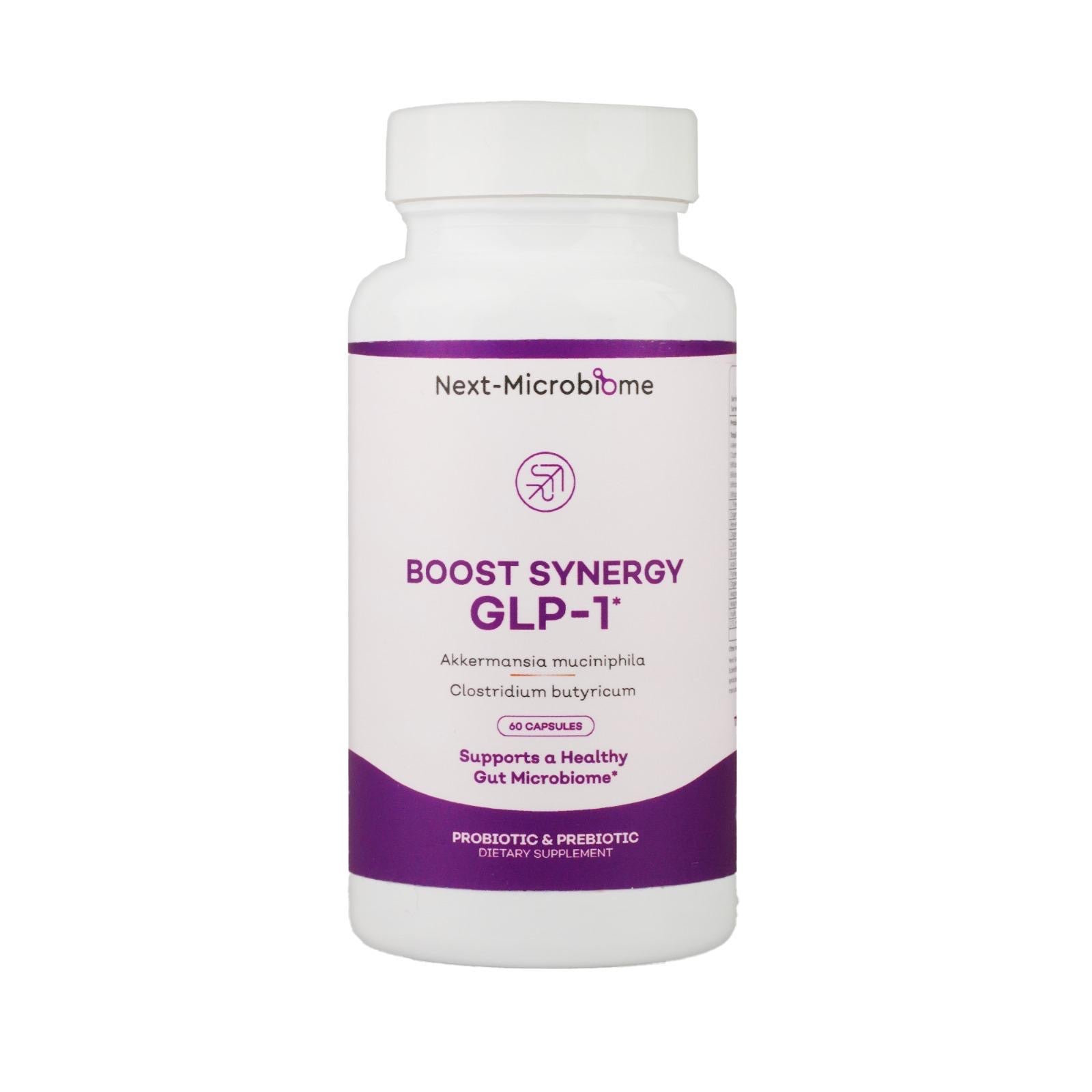

Formulations built around Akkermansia muciniphila reflect this approach by targeting the biological conditions that enable microbial function, rather than relying solely on colonization. When probiotics are designed to work in synergy with prebiotic substrates and microbial signaling pathways, their effects are more likely to persist beyond short-term supplementation.

Ecosystem-supporting probiotic approaches → Akkermansia Chewable

How Prebiotics and Probiotics Work Together

When prebiotics and probiotics are combined, they form a synbiotic relationship.

Prebiotics:

-

provide energy substrates

-

stimulate microbial fermentation

-

increase SCFA production

Probiotics:

-

introduce beneficial organisms

-

compete with opportunistic species

-

influence immune and metabolic signaling

Research summarized by Makki et al. in Cell Host & Microbe highlights that dietary fiber and microbial substrates are central regulators of microbial composition and function.

This interaction explains why feeding existing microbes often matters more than introducing new ones.

The Role of SCFAs in This Relationship

A key outcome of prebiotic fermentation is the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate.

SCFAs:

-

support gut lining integrity

-

regulate inflammation

-

influence metabolic and hormonal signaling

These microbial metabolites act as the functional link between fiber intake and host physiology.

This connection extends into broader metabolic regulation pathways — including interactions with GLP-1 and appetite signaling — as explored in Reset Metabolism Naturally with the Microbiome, SCFAs & GLP-1:

https://akkermansia.life/blogs/blog/reset-metabolism-naturally-microbiome-scfas-glp-1

The mechanistic role of SCFAs is explored further in the companion article:

Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): The Missing Link Between Fiber, Gut Health & Metabolism

(next in this cluster)

Choosing Between Prebiotics and Probiotics Is the Wrong Question

The real question is not which one is better, but how they are combined.

Adequate microbiome support requires:

-

appropriate bacterial inputs (probiotics)

-

sufficient microbial substrates (prebiotics)

-

dietary diversity and consistency

This systems-based view is central to the broader Human Microbiome Hub:

https://akkermansia.life/blogs/blog/human-microbiome-hub-oral-gut-axis-gut-brain-axis-microbiome-development

Practical Takeaway

-

Probiotics introduce beneficial bacteria

-

Prebiotics determine whether those bacteria can function

-

Long-term microbiome health depends on both

Supporting the microbiome is less about adding more organisms and more about creating the conditions that allow beneficial microbes to thrive.

When viewed through the lens of microbiome systems biology, probiotics act as inputs, while prebiotics act as the biological instructions that guide microbial behavior.

Scientific References

-

Gibson GR et al.

Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics.

Journal of Nutrition (1995).

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7782892/ -

Makki K et al.

The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease.

Cell Host & Microbe (2018).

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29902436/ -

Zmora N et al.

Personalized gut mucosal colonization resistance to probiotics.

Cell (2018).

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30193112/ -

Koh A et al.

From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites.

Cell (2016).

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27259147/

Written by Ali Rıza Akın

Microbiome Scientist, Author & Founder of Next-Microbiome

Ali Rıza Akın is a microbiome scientist with nearly 30 years of experience in biotechnology, translational research, and systems biology, spanning academic research and applied innovation in Silicon Valley.

His scientific work focuses on how microbial ecosystems interact with human physiology, with particular emphasis on:

-

gut-barrier structure and function

-

oral–gut microbiome interactions

-

dietary fiber fermentation and short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) metabolism

-

microbial regulation of metabolic, immune, and inflammatory signaling

He is the discoverer of Christensenella californii and a pioneer of function-driven, ecosystem-level microbiome science that moves beyond strain-centric probiotic models.

Ali Rıza Akın is the author of Bakterin Kadar Yaşa: İçimizdeki Evren – Mikrobiyotamız and a contributing author to Bacterial Therapy of Cancer (Springer), where his work explores microbial metabolites, host–microbe communication, and emerging therapeutic strategies.

Throughout his career, he has emphasized mechanistic clarity, evidence-based interpretation of peer-reviewed science, and responsible microbiome education, particularly in nutrition- and metabolism-related topics.