Leaky Gut Syndrome: What Science Says About the Gut

Leaky Gut Syndrome: What Science Really Says About Intestinal Permeability

“Leaky gut” has become one of the most discussed — and most misunderstood — topics in gut health. While the phrase is often used casually online, intestinal permeability is a real, scientifically recognized biological process that plays a central role in digestion, immune regulation, and systemic inflammation.

In biomedical research, intestinal permeability has been studied for decades in relation to immune activation, metabolic disease, and inflammatory disorders. Foundational work has established how gut barrier regulation influences both local and systemic immune signaling (Turner, 2009; Bischoff et al., 2014).

This article explains what leaky gut actually means, how it differs from normal intestinal permeability, what contributes to gut barrier disruption, and how current science approaches supporting gut barrier function — without fear-based claims or quick-fix promises.

Summary

Leaky gut syndrome is a commonly used, non-clinical term for increased intestinal permeability, a measurable physiological process involving impaired regulation of the intestinal barrier. Under healthy conditions, the gut lining selectively allows nutrients to pass while limiting the movement of microbes, toxins, and inflammatory molecules into circulation. When this regulation is disrupted, permeability may increase, contributing to immune activation and low-grade inflammation. Intestinal permeability exists on a continuum and is not a diagnosis by itself. Scientific research shows that gut barrier regulation depends on coordinated interactions between epithelial tight junctions, the protective mucus layer, and microbiome-derived signaling molecules. Sustainable gut barrier support focuses on restoring microbial balance, dietary diversity, circadian rhythm stability, and immune–microbial communication rather than attempting to “seal” the gut.

What Is Leaky Gut Syndrome?

Leaky gut syndrome refers to increased intestinal permeability, a condition in which the tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells become less regulated.

Under healthy conditions, the intestinal lining acts as a selective barrier:

-

Nutrients pass through efficiently

-

Pathogens, toxins, and undigested particles are restricted

When this barrier becomes dysregulated, larger molecules may pass into circulation, potentially triggering immune activation and low-grade inflammation. This mechanism has been extensively described in the literature on intestinal physiology (Turner, 2009).

Importantly, intestinal permeability exists on a spectrum and is not, by itself, a medical diagnosis.

Intestinal Permeability vs. “Leaky Gut”

The intestinal barrier is not meant to be completely sealed. Controlled permeability is essential for nutrient absorption and immune surveillance.

Problems arise when permeability becomes chronic, excessive, or poorly regulated, often alongside inflammation or microbiome disruption. According to Bischoff et al. (2014), dysregulated intestinal permeability is increasingly recognized as a contributing factor — not a sole cause — in a range of chronic inflammatory and metabolic conditions.

In simple terms:

-

Permeability = normal physiology

-

Leaky gut = loss of regulation

For a detailed scientific comparison, see:

https://akkermansia.life/blogs/blog/intestinal-permeability-vs-leaky-gut-what-science-says

What Contributes to Increased Intestinal Permeability?

Research indicates that increased intestinal permeability is multifactorial, with several overlapping contributors rather than a single cause.

1. Microbiome Imbalance

Loss of microbial diversity — particularly mucus-associated bacteria — has been strongly linked to impaired barrier signaling, mucus thinning, and epithelial vulnerability (Chelakkot et al., 2018).

2. Chronic Inflammatory Signaling

Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and interferon-γ can alter tight junction protein expression and localization, weakening barrier regulation (Turner, 2009).

3. Stress and Circadian Disruption

Stress hormones and circadian misalignment influence gut permeability through neuro-immune pathways, cortisol signaling, and altered microbial rhythms.

4. Dietary Patterns

Low fiber intake and ultra-processed diets reduce microbial metabolite production, including short-chain fatty acids that support epithelial energy metabolism and tight junction integrity.

5. Repeated Antibiotic Exposure

Antibiotics can reduce beneficial microbes involved in mucus regulation and epithelial renewal, indirectly affecting long-term barrier stability.

Commonly Reported Symptoms

There is no single symptom profile. Increased intestinal permeability has been studied in association with, but not as a direct cause of:

-

Digestive discomfort

-

Food sensitivities

-

Skin manifestations

-

Fatigue

-

Brain fog

-

Immune dysregulation

Because these symptoms are non-specific, scientific literature consistently emphasizes contextual interpretation rather than self-diagnosis.

How the Gut Barrier Is Maintained

The intestinal barrier is supported by three interdependent systems:

-

Epithelial tight junctions regulating paracellular transport

-

The mucus layer, which physically separates microbes from epithelial cells

-

Microbial signaling and metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids

Chelakkot et al. (2018) demonstrate that disruption in any one of these systems can destabilize the others. Effective gut barrier support, therefore, focuses on system-level coordination rather than isolated interventions.

Supporting Gut Barrier Health Naturally

Scientific evidence suggests that gut barrier support is most effective when it focuses on environmental and microbial regulation, rather than aggressive or suppressive strategies.

Commonly supported approaches include:

-

Supporting microbial diversity

-

Consuming diverse dietary fibers

-

Reducing chronic stress

-

Protecting sleep and circadian rhythms

-

Avoiding unnecessary antimicrobial overuse

Research consistently favors restoration and regulation over attempts to forcibly “repair” or “seal” the gut barrier.

Supporting the Gut Barrier Through the Microbiome

Gut barrier function does not operate in isolation. It is closely connected to the broader human microbiome, including oral microbes, gut-resident bacteria, and the metabolites they produce. Increasing evidence shows that microbial diversity, mucus-associated species, and oral–gut microbial signaling play key roles in long-term barrier regulation (Chelakkot et al., 2018).

For a deeper, science-based overview, visit the Akkermansia Microbiome Hub:

https://akkermansia.life/blogs/blog/akkermansia-microbiome-hub-gut-lining-oral-gut-axis-natural-ways-to-support-akkermansia

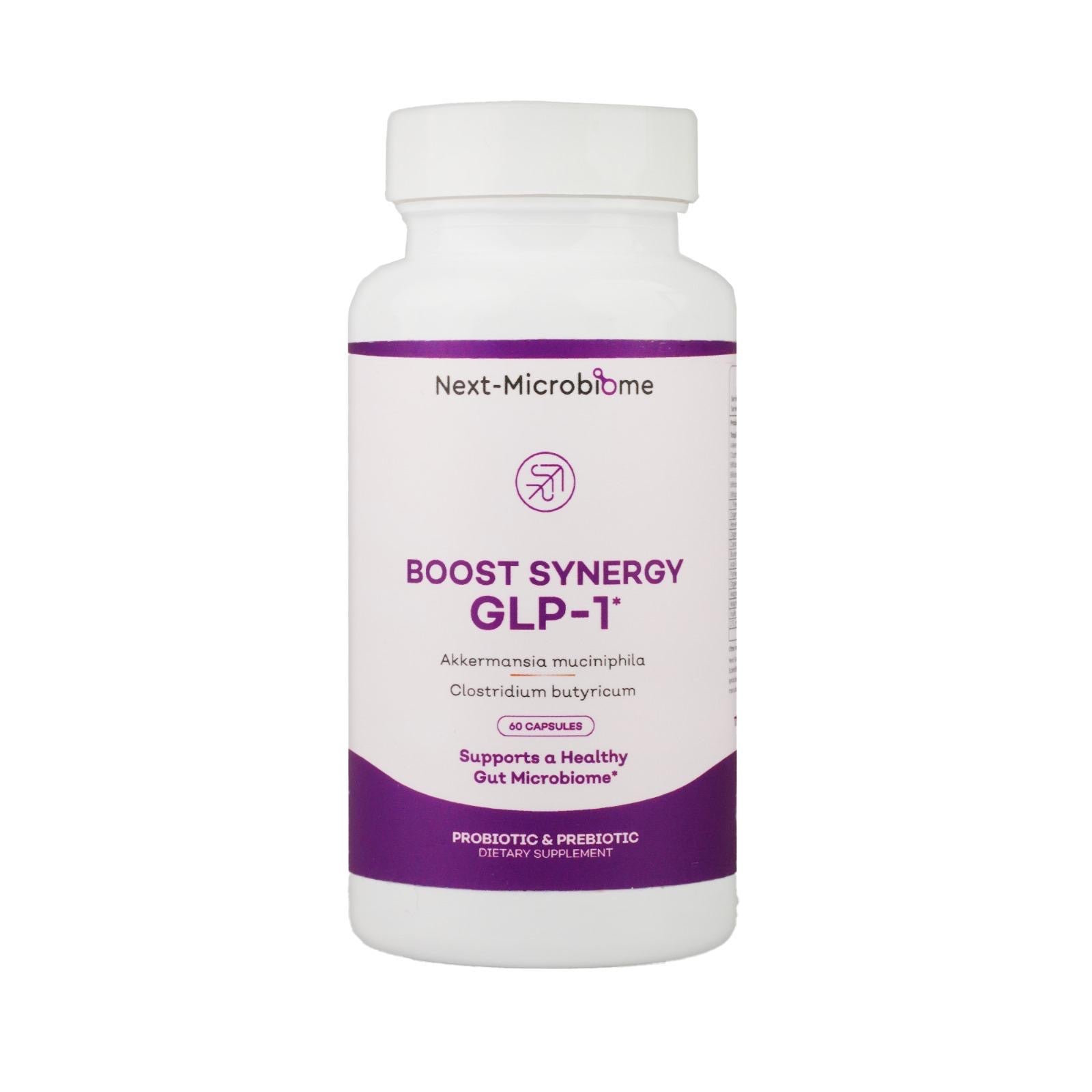

Some individuals choose microbiome-focused formulations designed to support mucus-associated bacteria and microbial signaling as part of a broader gut barrier strategy. These approaches are intended to complement diet, sleep, and lifestyle factors rather than replace them:

https://akkermansia.life/products/probiome-novo-2-0-akkermensia-chewable-probiotics

Because gut barrier regulation is also linked to microbial metabolites and metabolic signaling, some people explore microbiome-based metabolic support strategies alongside nutritional and lifestyle changes:

https://akkermansia.life/products/boost-synergy-glp-1-probiotic-akkermansia-muciniphila-clostridium-butyricum-hmo-ashwagandha-supports-oral-microbiome-digestive-wellness-gut-health-for-men-women-60-capsules-1-pack

Frequently Asked Questions

Is leaky gut a real medical condition?

Increased intestinal permeability is a well-studied physiological process. “Leaky gut” is a non-clinical term describing dysregulation of this process.

Can leaky gut be tested?

Clinical tests exist, but results require professional interpretation and clinical context.

Does everyone have intestinal permeability?

Yes. Controlled permeability is essential for nutrient absorption.

Can probiotics repair leaky gut?

No single supplement repairs the gut. Microbiome-focused strategies support signaling and balance over time.

How long does gut barrier support take?

Meaningful microbiome and barrier changes typically occur over months, not days.

What foods support gut barrier health?

Fiber-rich plant foods and polyphenol-containing foods that support microbial metabolism.

Key Takeaways

-

Intestinal permeability is real, measurable, and biologically necessary

-

“Leaky gut” refers to dysregulated permeability, not structural damage alone

-

Gut barrier health depends on microbial signaling, mucus biology, and immune balance

-

Sustainable improvement comes from ecosystem-level support

-

Science favors regulation and restoration over restriction

Scientific References

-

Turner JR.

Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease.

Nature Reviews Immunology (2009).

PMID: 19855405

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19855405/ -

Bischoff SC, et al.

Intestinal permeability – a new target for disease prevention and therapy.

BMC Gastroenterology (2014).

PMID: 25407511

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25407511/ -

Chelakkot C, Ghim J, Ryu SH.

Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications.

Experimental & Molecular Medicine (2018).

PMID: 30115904

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30115904/

Author

Written by Ali Rıza Akın

Microbiome Scientist, Author & Founder of Next-Microbiome

Ali Rıza Akın is a microbiome scientist with nearly 30 years of experience in translational biotechnology, systems biology, and applied microbiome research in Silicon Valley. His work bridges fundamental microbial physiology with real-world clinical and consumer applications, focusing on how microbial ecosystems regulate human health.

His scientific expertise includes:

-

Gut barrier structure and intestinal permeability

-

Mucus-associated microbial ecology

-

Oral–gut microbiome communication

-

Microbiome-driven immune and metabolic signaling

-

Short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) biology

Ali Rıza Akın is the discoverer of Christensenella californii, a human-associated bacterial species described in the scientific literature and linked to metabolic health and microbiome diversity. His research contributions appear in peer-reviewed journals and authoritative reference texts, including Bacterial Therapy of Cancer (Springer).

He is also the author of Bakterin Kadar Yaşa: İçimizdeki Evren: Mikrobiyotamız, a science-based book translating complex microbiome research into accessible public understanding.

Through Next-Microbiome, his work focuses on evidence-based microbiome innovation, emphasizing scientific rigor, regulatory compliance, and long-term ecosystem health rather than short-term trends.