Leaky Gut Syndrome: Symptoms, Causes & Gut Repair

Leaky Gut Syndrome: Symptoms, Causes, and How to Repair the Gut Barrier Naturally

The term “leaky gut syndrome” is commonly used to describe a state in which the intestinal barrier becomes more permeable than normal. While it is not a formal medical diagnosis, a growing body of scientific research shows that changes in intestinal permeability are associated with digestive discomfort, immune activation, metabolic imbalance, and systemic inflammation.

To understand leaky gut properly, it is essential to begin with the science of the intestinal barrier itself. This article builds directly on the foundational explanation here:

Gut Barrier Health: Science of Intestinal Integrity

https://akkermansia.life/blogs/blog/gut-barrier-health-science-of-intestinal-integrity

Summary

Leaky gut syndrome is a non-medical term commonly used to describe increased intestinal permeability, a physiological state in which the gut barrier allows larger molecules to pass more easily into circulation. Scientific research shows that gut barrier integrity depends on tight junction proteins, a protective mucus layer, microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and balanced immune signaling. Disruptions in diet, chronic stress, inflammation, circadian rhythm misalignment, and microbial imbalance may influence this barrier over time, as described in mechanistic reviews by Chelakkot et al. (Korean Science Journal, 2018) and expert consensus papers by Bischoff et al. (BMC Gastroenterology, 2014). Supporting gut barrier health focuses on fiber-driven SCFA production, mucus layer integrity, microbial–host interactions, and lifestyle consistency rather than quick fixes.

What Is Intestinal Permeability?

The intestinal barrier is a dynamic biological interface composed of:

-

A single layer of epithelial cells

-

Tight junction proteins that regulate passage between cells

-

A protective mucus layer

-

A diverse microbial ecosystem that supports mucosal integrity

When this system functions correctly, nutrients are absorbed efficiently while bacteria, toxins, and inflammatory molecules are kept out of circulation.

Research on intestinal barrier biology shows that tight junction proteins function as dynamic regulators rather than static seals. Disruption of tight junction structure and signaling has been consistently linked to increased intestinal permeability and immune activation in both experimental and clinical settings, as reviewed by Chelakkot, Ghim, and Ryu (Korean Science Journal, 2018).

Common Symptoms Associated With Increased Gut Permeability

Symptoms associated with increased intestinal permeability are often non-specific and may overlap with those of other conditions.

Digestive Symptoms

-

Bloating or gas

-

Irregular bowel movements

-

Abdominal discomfort after meals

Systemic or Extra-Digestive Symptoms

-

Fatigue

-

Brain fog

-

Joint stiffness

-

Skin irritation

-

Heightened sensitivity to foods

These symptoms do not confirm leaky gut on their own but may occur alongside barrier dysfunction in certain physiological contexts, as discussed in clinical reviews of intestinal permeability by Bischoff et al. (BMC Gastroenterology, 2014).

What Causes the Gut Barrier to Break Down?

1. Dietary Patterns

Diets low in fermentable fiber and high in ultra-processed foods may reduce the production of beneficial microbial metabolites. In contrast, dietary fiber that supports microbial fermentation helps maintain epithelial health and tight junction stability through SCFA signaling, as demonstrated by Koh et al. (Cell, 2016).

2. Chronic Stress

Stress influences gut motility, immune signaling, and microbial balance. Elevated cortisol levels may alter mucus secretion and epithelial renewal, thereby indirectly affecting barrier resilience — a mechanism frequently observed in gut–immune interactions research.

3. Microbial Imbalance (Dysbiosis)

The gut barrier depends on specific microbes that interact with the mucus layer and epithelial surface. Reduced abundance of beneficial microbes can weaken this protective interface over time, increasing susceptibility to permeability changes.

4. Inflammation

Local or systemic inflammation may downregulate tight junction proteins. Expert consensus literature emphasizes that increased intestinal permeability is best understood as a functional biological state, influenced by immune activity, stress, and microbial interactions rather than a standalone disease, as summarized by Bischoff et al. (BMC Gastroenterology, 2014).

How to Support Gut Barrier Health Naturally

Supporting the gut barrier is a systems-level process, not a quick fix. Research-aligned strategies focus on reinforcing the biological mechanisms that maintain integrity.

1. Increase Fermentable Fiber Intake

The relationship between dietary fiber and gut barrier health is largely mediated by short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced during microbial fermentation. SCFAs serve as energy sources for epithelial cells, strengthen tight junctions, and promote mucosal resilience, as shown in foundational work by Koh et al. (Cell, 2016).

Learn more here:

Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)

https://akkermansia.life/blogs/blog/short-chain-fatty-acids-scfas-gut-barrier-metabolism-health

2. Support the Mucus Layer

The mucus layer forms a protective buffer between microbes and the intestinal wall. Certain microbes interact directly with this layer and help regulate its renewal. Experimental work by Plovier et al. (Nature Medicine, 2017) demonstrated that Akkermansia muciniphila and its membrane components influence mucus layer thickness and epithelial signaling, highlighting the importance of mucus-associated microbes in barrier maintenance.

3. Align Stress and Circadian Rhythms

Gut barrier function follows circadian biology. Irregular sleep, chronic stress, and disrupted daily rhythms can impair epithelial repair and immune coordination, indirectly weakening barrier integrity.

4. Consider Evidence-Informed Supportive Formulations

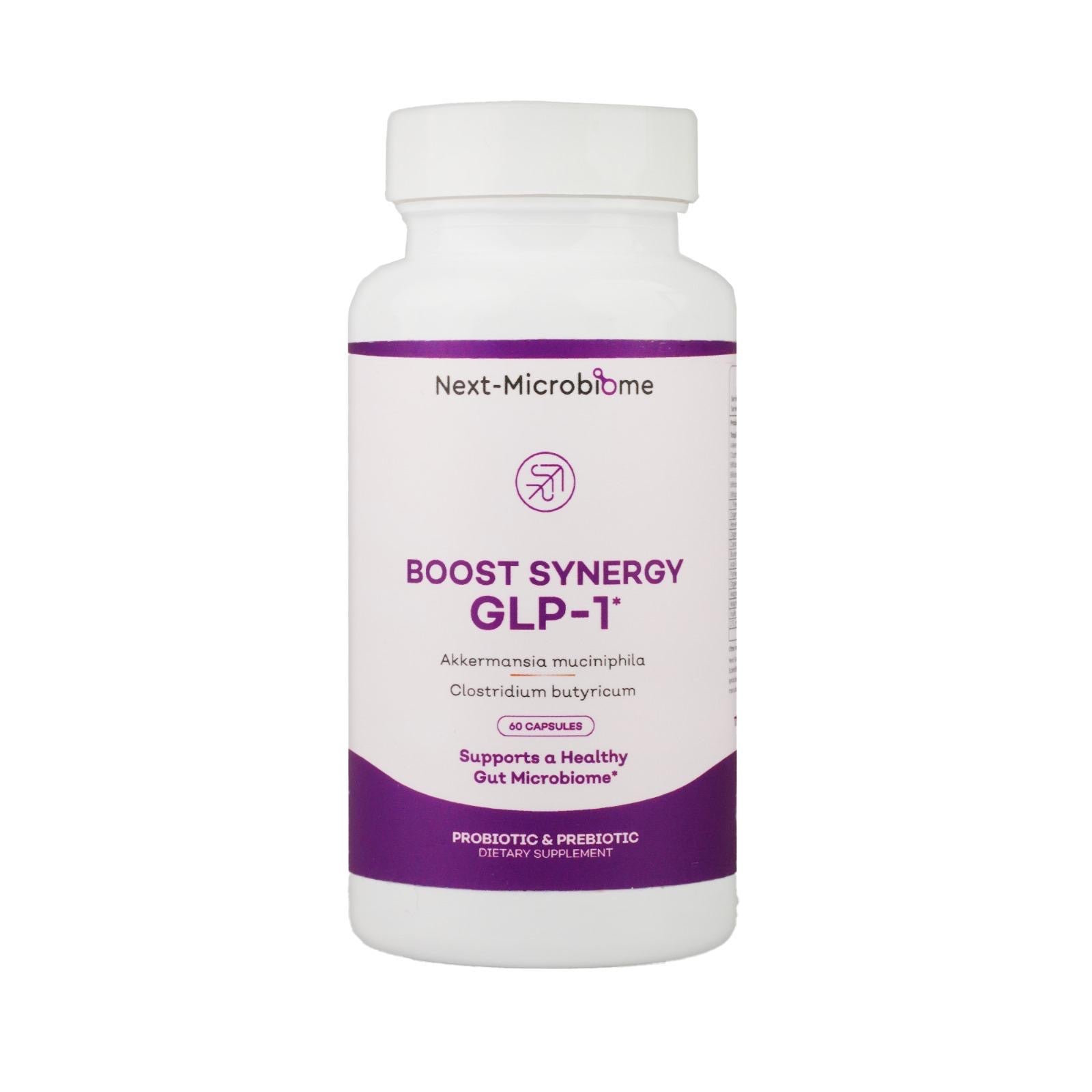

Some microbiome-focused formulations are designed to complement barrier-supportive pathways by encouraging beneficial microbial activity, supporting SCFA production, and reinforcing host–microbe interactions. Mechanistic alignment matters more than marketing claims.

How the Oral–Gut Axis Influences Leaky Gut

Digestion begins in the mouth. Oral microbes interact with food, saliva, and immune tissues before nutrients reach the intestine. Disruptions in the oral microbiome may influence downstream gut microbial balance and mucus layer interactions.

For a deeper explanation of this connection, see:

Oral Microbiome and Gut Health

https://akkermansia.life/blogs/blog/oral-microbiota-gut-health-how-the-mouth-shapes-the-entire-microbiome

Frequently Asked Questions

Is leaky gut a real condition?

“Leaky gut” is not a formal diagnosis, but intestinal permeability is a measurable physiological phenomenon that has been studied extensively in research, including mechanistic and clinical reviews by Chelakkot et al. (2018) and Bischoff et al. (2014).

Can diet alone improve gut barrier health?

Diet is foundational, particularly through fiber-driven SCFA production, but stress regulation, sleep, and microbial balance also influence outcomes.

How long does it take to support the gut barrier?

Biological changes typically occur over weeks to months and vary by individual. Consistency is more important than speed.

Conclusion

Leaky gut is best understood as a pattern of altered intestinal permeability rather than a disease. By focusing on gut barrier biology — including tight junctions, mucus layer health, microbial metabolites, and circadian alignment — it is possible to support intestinal integrity in a natural, evidence-based way.

For the full scientific foundation, revisit:

Gut Barrier Health: Science of Intestinal Integrity

https://akkermansia.life/blogs/blog/gut-barrier-health-science-of-intestinal-integrity

References

Chelakkot, C., Ghim, J., & Ryu, S. H. (2018).

Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Korean Science Journal.

https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO201827055061329.page

Bischoff, S. C., et al. (2014).

Intestinal permeability — a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterology (PMC full text).

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4253991/

Koh, A., De Vadder, F., Kovatcheva-Datchary, P., & Bäckhed, F. (2016).

From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27259147/

Plovier, H., et al. (2017).

A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila, or from the pasteurized bacterium, improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nature Medicine.

https://www.nature.com/articles/nm.4236

About the Author

Ali Rıza Akın is a microbiome scientist, biotechnology entrepreneur, and science communicator with nearly 30 years of experience in microbiome research, translational biotechnology, and applied microbial science.

His work focuses on:

-

intestinal barrier integrity and epithelial biology

-

mucus layer regulation and host–microbe interactions

-

short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) metabolism

-

oral–gut microbiome communication

-

microbiome-driven immune and metabolic signaling

Ali Rıza Akın is the discoverer of Christensenella californii, a human-associated bacterial species linked to metabolic health and microbiome diversity. His work has appeared in peer-reviewed publications and reference volumes, including Bacterial Therapy of Cancer (Springer).

He is also the author of Bakterin Kadar Yaşa: İçimizdeki Evren – Mikrobiyotamız, translating complex microbiome science into accessible, evidence-based explanations.

This content is for educational purposes only and does not replace professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.